How Was the Canal Built?

Digging the Canal

Most sections of the dry land that was to become the Erie Canal consisted of dense forests in untouched wilderness and included areas of massive rock. Since builder had only human and animal power (horses and mules) to clear the land and dig the canal, building the canal was a monumental effort (Bernstein, 2005). There were no current technologies in use for the builders to use to make the job easier or faster. However, the workers created machines such as a "stump puller" using wheels, ropes, and the strength of horses to pull up stumps and modified farm plows to allow for faster brush clearing and digging. Because of the ingenuity of the workers, the project was dubbed the "Erie School of Engineers" and the crew leaders became some of America's first hydraulic engineers as they learned how to manage land and water on the job (Root, n.d.).

To clear the rocks, builders used a new blasting powder called Dupont's Blasting Powder. It was more powerful that black powder which was previously used but paled in comparison to the dynamite that is used today (McNeese, 1993). The only part of the landscape that was not covered by forest and rock consisted of swamps and marshland teeming with insects and thick mud. Though there were many other canals built in America and Europe at that time, there was no precedent in modern history that matched the size and difficulty of the building of the Erie Canal (Bernstein, 2005).

Most sections of the dry land that was to become the Erie Canal consisted of dense forests in untouched wilderness and included areas of massive rock. Since builder had only human and animal power (horses and mules) to clear the land and dig the canal, building the canal was a monumental effort (Bernstein, 2005). There were no current technologies in use for the builders to use to make the job easier or faster. However, the workers created machines such as a "stump puller" using wheels, ropes, and the strength of horses to pull up stumps and modified farm plows to allow for faster brush clearing and digging. Because of the ingenuity of the workers, the project was dubbed the "Erie School of Engineers" and the crew leaders became some of America's first hydraulic engineers as they learned how to manage land and water on the job (Root, n.d.).

To clear the rocks, builders used a new blasting powder called Dupont's Blasting Powder. It was more powerful that black powder which was previously used but paled in comparison to the dynamite that is used today (McNeese, 1993). The only part of the landscape that was not covered by forest and rock consisted of swamps and marshland teeming with insects and thick mud. Though there were many other canals built in America and Europe at that time, there was no precedent in modern history that matched the size and difficulty of the building of the Erie Canal (Bernstein, 2005).

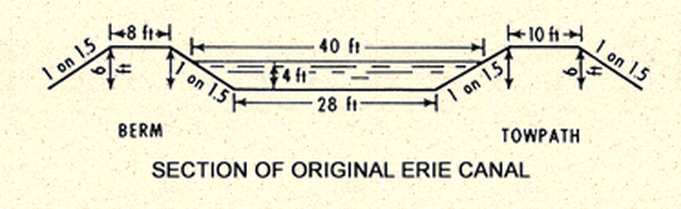

Section of Original Erie Canal. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

Section of Original Erie Canal. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

Though the canal was later enlarged to accommodate bigger, heavier boats, the first canal was dug 4 feet deep and 40 feet wide. This allowed floating boats to carry 30 tons of cargo or passengers (Sadowski, 2012). Alongside the canal on one side was a wide towpath where horses or mules pulled ropes attached to the boats, which was the method used in England's canals at the time. Along the other side was a berm to protect the canal (Bernstein, 2005).

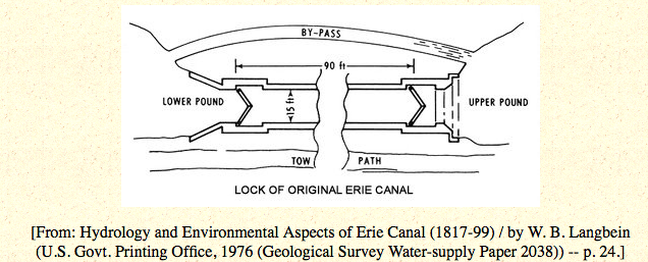

Lock of Original Erie Canal. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

Lock of Original Erie Canal. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

Locks

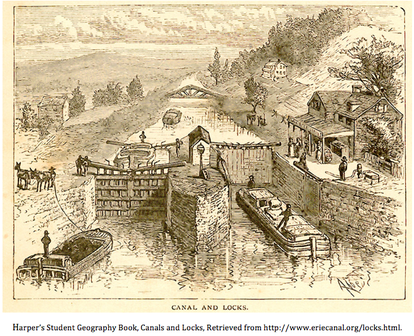

The type of lock gates used in the Erie Canal was created by Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci in the first half of the 1500s. He designed a gate with two panels that came together in a “V” shape and faced upstream so that the pressure from the water push the gates together to make a tight fit (Bernstein, 2005). These gates are called “miter-V gates” and are still used in most canal systems today (Gertz, 2013).

To build the lock sections of the canal, builders initially thought to use either stone or wood; however, both materials were problematic. The wood would rot because of exposure to water and the stones had to be secured in place with a special cement that used an expensive, imported main ingredient called trass. A search was conducted to see if this ingredient might be found in local land. Fortunately, trass was located in land near the canal path and the decision to use stone for the sides of the locks was finalized (McNeese, 1993).

The type of lock gates used in the Erie Canal was created by Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci in the first half of the 1500s. He designed a gate with two panels that came together in a “V” shape and faced upstream so that the pressure from the water push the gates together to make a tight fit (Bernstein, 2005). These gates are called “miter-V gates” and are still used in most canal systems today (Gertz, 2013).

To build the lock sections of the canal, builders initially thought to use either stone or wood; however, both materials were problematic. The wood would rot because of exposure to water and the stones had to be secured in place with a special cement that used an expensive, imported main ingredient called trass. A search was conducted to see if this ingredient might be found in local land. Fortunately, trass was located in land near the canal path and the decision to use stone for the sides of the locks was finalized (McNeese, 1993).

When boats approached a lock, the first gates would be opened. Mules or horses pulled the boat into the lock. The gates behind the boat were closed. Then underwater openings called sluices in the gates in front of the boat were opened to either allow water in so that the boat would rise up to the higher level of the next part of the canal or it would allow water out so that the boat would sink to the lower level of the next part of the canal. Then the boat would be pulled out of the canal and the gates closed behind it and the water let in or out of the lock so that it would be ready for the next boat (Sadowski, 2012.)

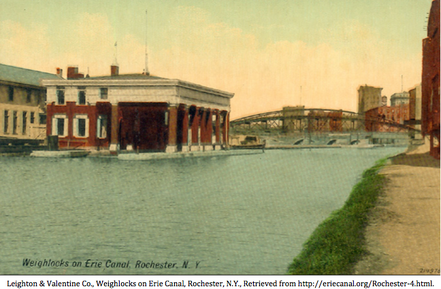

Weighlocks and Tolls

In order to determine how much toll a boat had to pay to travel parts of the Eric Canal, weighlocks were created. After a boat entered the lock, the weighmaster measured the height of the resulting higher level of water and calculated the toll based on this displacement of water and the rate established for the type of cargo carried on the boat (Making it work: The weighlock, 2003). The tolls that were collected paid for the canal and the first enlargement of it. There were 5 weighlocks along the canal so a boat only has to be weighed and pay a toll at one along its trip. These were located in Syracuse, Albany, West Troy, Utica, and Rochester (Welcome to the Syracuse weighlock, 2013). Later updates to the canal included scales that measured the weight of the boats after the water was drained from a lock and compared that weight to the weight of the boat empty, a measurement that had been previously determined in the spring of each year (Making it work: The weighlock, 2003).

To see how this updated way of weighing boats and calculating the toll worked, play the Erie Canal Museum’s Syracuse Weighmaster Game at the link below.

In order to determine how much toll a boat had to pay to travel parts of the Eric Canal, weighlocks were created. After a boat entered the lock, the weighmaster measured the height of the resulting higher level of water and calculated the toll based on this displacement of water and the rate established for the type of cargo carried on the boat (Making it work: The weighlock, 2003). The tolls that were collected paid for the canal and the first enlargement of it. There were 5 weighlocks along the canal so a boat only has to be weighed and pay a toll at one along its trip. These were located in Syracuse, Albany, West Troy, Utica, and Rochester (Welcome to the Syracuse weighlock, 2013). Later updates to the canal included scales that measured the weight of the boats after the water was drained from a lock and compared that weight to the weight of the boat empty, a measurement that had been previously determined in the spring of each year (Making it work: The weighlock, 2003).

To see how this updated way of weighing boats and calculating the toll worked, play the Erie Canal Museum’s Syracuse Weighmaster Game at the link below.

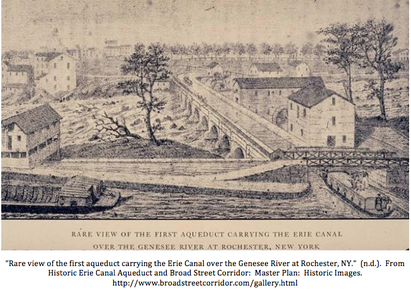

Aqueducts

Aqueducts were built along the Erie Canal to allow the water in the canal to move over rivers or valleys. The aqueducts was basically a bridge over the water or valley that had a canal and towpath built into it. It looked like an elevated river.

Aqueducts have been used for centuries to move water from natural sources to cities and towns to be used as drinking water (Aqueduct, 2013). Canal developers used the same technology to build the water bridges to allow the canals to stay at the same elevation despite the rises and drops in elevation associate with rivers and valley. The aqueduct in the above picture is the Genesee Aqueduct over the Mohawk River. It 802 feet long and created using 11 arches (McNeese, 1993).

Aqueducts were built along the Erie Canal to allow the water in the canal to move over rivers or valleys. The aqueducts was basically a bridge over the water or valley that had a canal and towpath built into it. It looked like an elevated river.

Aqueducts have been used for centuries to move water from natural sources to cities and towns to be used as drinking water (Aqueduct, 2013). Canal developers used the same technology to build the water bridges to allow the canals to stay at the same elevation despite the rises and drops in elevation associate with rivers and valley. The aqueduct in the above picture is the Genesee Aqueduct over the Mohawk River. It 802 feet long and created using 11 arches (McNeese, 1993).

Workers

The Commissioners of the Canal Fund, a group of high-level government employees who were charged with managing the finances of the building of the canal, made numerous contracts with local people to build small parts of the canal. The local people knew the land best and had the most experience clearing it as they had already done to create their farms and homes. Also, since canal-building was relatively new in the country, there were not many people who were experts in building. Having numerous small groups working on different sections shielded the government from public disfavor if a large contractor were hired and subsequently bungled large sections of the canal. Possibly most important to the success of the canal, local people took pride in building the section of the canal that was on or near their land and wanted to do the best job possible. The workers were paid $12 a month for their labor; however, food and basic lodging were sometimes provided. During the summer months mosquitoes were a terrible problem for workers and at least 1000 contracted malaria. There were no effective medicines for malaria at the time and many men died. Because of this, some work sites were shut down in summer months in order to wait for the cold weather to kill the insects. Thousands of Irish immigrant workers were also integral to the success of the building project but were not hired on until later in the project (Bernstein, 2005).

The Commissioners of the Canal Fund, a group of high-level government employees who were charged with managing the finances of the building of the canal, made numerous contracts with local people to build small parts of the canal. The local people knew the land best and had the most experience clearing it as they had already done to create their farms and homes. Also, since canal-building was relatively new in the country, there were not many people who were experts in building. Having numerous small groups working on different sections shielded the government from public disfavor if a large contractor were hired and subsequently bungled large sections of the canal. Possibly most important to the success of the canal, local people took pride in building the section of the canal that was on or near their land and wanted to do the best job possible. The workers were paid $12 a month for their labor; however, food and basic lodging were sometimes provided. During the summer months mosquitoes were a terrible problem for workers and at least 1000 contracted malaria. There were no effective medicines for malaria at the time and many men died. Because of this, some work sites were shut down in summer months in order to wait for the cold weather to kill the insects. Thousands of Irish immigrant workers were also integral to the success of the building project but were not hired on until later in the project (Bernstein, 2005).

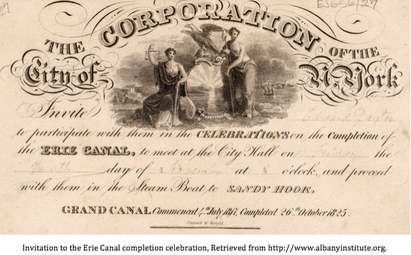

Completion

Governor DeWitt Clinton had projected to have the Erie Canal completed by 1823. However, by 1825 the entire project was completed and it was deemed the engineering marvel of its time. The celebration marking the completion began on October 26 and continued until November 4th and included many boats with various dignitaries parading east and west on the canal and making speeches in towns along the way. A lavish ball was held on November 7 and ended the long celebration. The Erie Canal was hailed as a "Wedding of Waters" (Bernstein, 2005).

Governor DeWitt Clinton had projected to have the Erie Canal completed by 1823. However, by 1825 the entire project was completed and it was deemed the engineering marvel of its time. The celebration marking the completion began on October 26 and continued until November 4th and included many boats with various dignitaries parading east and west on the canal and making speeches in towns along the way. A lavish ball was held on November 7 and ended the long celebration. The Erie Canal was hailed as a "Wedding of Waters" (Bernstein, 2005).

Boats

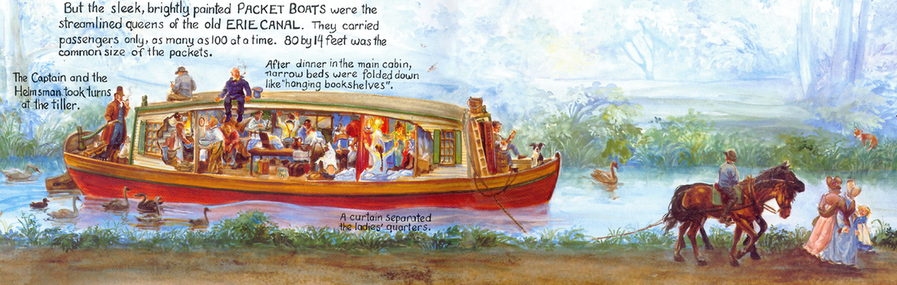

There were many types of boats used on the canal. Boats that carried only passengers were called packet boats. Other boats called lakers and bullheads carried only cargo while line boats carried both cargo and passengers. There were also work scow boats, also known as “hurry-up boats,” that traveled to areas of the canal that needed repairs. Since the work scow boats were servicing the canal, they were not weighed (Welcome to the Syracuse weighlock, 2013).

There were many types of boats used on the canal. Boats that carried only passengers were called packet boats. Other boats called lakers and bullheads carried only cargo while line boats carried both cargo and passengers. There were also work scow boats, also known as “hurry-up boats,” that traveled to areas of the canal that needed repairs. Since the work scow boats were servicing the canal, they were not weighed (Welcome to the Syracuse weighlock, 2013).

C. Harness, (1995). The Amazing, Impossible Erie Canal. New York : Macmillan Books for Young Readers. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

C. Harness, (1995). The Amazing, Impossible Erie Canal. New York : Macmillan Books for Young Readers. Cited in Sadowski, 2012.

Low bridges were built over the canal to allow farmers access to their fields which had been cut by the canal. Some were only 7 1/2 feet up from the ground which did not allow much room between the top of the boats and the bottom of the bridge. Frequently, boat crew would warn passengers of an upcoming bridge by shouting, "Low bridge!" so that passengers would not be knocked off the boat (Welcome to the Syracuse weighlock, 2013).

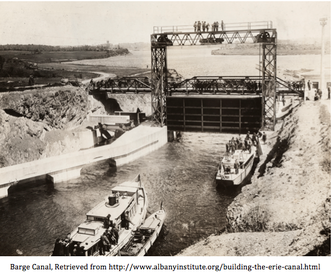

From then until now, briefly

After the completion of the main Erie Canal in 1825, canal traffic increased tremendously. Over the next 37 years more canals are built to connect larger cities to the main Erie Canal. The Erie, Oswego, and Champlain canals are the most popular and are enlarged to allow for increased traffic and bigger boats that can carry more cargo. In the 1870s, however, some of the smaller canal that had recently been built were closed because of low usage and cost. The year 1880 was the most successful year for the Erie Canal based on the amount of cargo transported on it. In 1882, New York stopped collecting tolls for passage on the Erie Canal. In the early 1900s, the New York State Barge Canal System was created to allow self-propelled boats to travel the canals. The Barge Canal System replaced the Erie Canal and 3 other feeder canals and included electrically powered locks. The canal faced stiff competition from railroad lines and from the St. Lawrence Seaway which was completed in 1959, providing a direct shipping route from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. In 2000, Congress created the Erie Canalway National Heritage corridor to commemorate the historic accomplishment of the canal's creation and the impact it had on the surrounding communities. Today the canal system is still in use primarily for recreational travel but also for commercial purposes (Erie Canalway Brochure, 2008).

After the completion of the main Erie Canal in 1825, canal traffic increased tremendously. Over the next 37 years more canals are built to connect larger cities to the main Erie Canal. The Erie, Oswego, and Champlain canals are the most popular and are enlarged to allow for increased traffic and bigger boats that can carry more cargo. In the 1870s, however, some of the smaller canal that had recently been built were closed because of low usage and cost. The year 1880 was the most successful year for the Erie Canal based on the amount of cargo transported on it. In 1882, New York stopped collecting tolls for passage on the Erie Canal. In the early 1900s, the New York State Barge Canal System was created to allow self-propelled boats to travel the canals. The Barge Canal System replaced the Erie Canal and 3 other feeder canals and included electrically powered locks. The canal faced stiff competition from railroad lines and from the St. Lawrence Seaway which was completed in 1959, providing a direct shipping route from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. In 2000, Congress created the Erie Canalway National Heritage corridor to commemorate the historic accomplishment of the canal's creation and the impact it had on the surrounding communities. Today the canal system is still in use primarily for recreational travel but also for commercial purposes (Erie Canalway Brochure, 2008).